Bob Mould, of course, was the guitarist/singer/songwriter of Husker Du, a band many consider to be groundbreaking for their ability to combine intense sonic power, melodic "pop-like" song-structure, and emotionally revealing lyrics. Instead of shedding the restrictive confines of hardcore (as fellow Minneapolitans the Replacements did on their journey toward wider acceptance), Husker Du simply redefined and expanded the limits of that musical form.

But Husker Du fell apart in 1988 after eight albums, much critical acclaim, and budding commercial success. It's been reported that a major contributing factor to the breakup was the drug abuse of Grant Hart, the band's drummer/singer/songwriter.

Bob Mould's first solo album, Workbook, was composed during the year following the dissolution of Husker Du. During that period, Mould isolated himself in his Minnesota home, seeing few people, writing letters, composing music. The pain resulting from the breakup of the band he'd been piloting for nearly a decade, as well as the alienation and loneliness he felt in the following year, is well documented on Workbook.

For example, on "Brasilia Crossed With Trenton," Mould sings, "I knew that this would happen sooner or later/ That I'd get disillusioned with it all/ Just throw my hands up to the sky and say/ Oh Lord, what happened, what happened/ To make things run this way?" And on "Compositions For The Young And Old" he sings, "I hear the weatherman/ He says 'It looks like rain for a while'/ I guess I'll have to stay inside/ Make peanut butter sandwiches and cry."

Despite the sadness and loneliness expressed in Workbook, Mould never succumbs to complete hopelessness— the pain never approaches resignation. On Lonely Afternoon" he sings, "Well, the silence in this house/ It echoes in this house/ I pull myself together, say/ 'Today I will get out'...A giant vision in the distance/ Chase that rainbow down/ I hear a pound, pound, pounding in my chest/ I hear a knock, a knocking sound/ It's the sliver flowing through my veins/ It's a sign that I'm alive/ You're so lucky, oh my friend, so lucky/ You're lucky just to be alive."

Throughout the album, even when singing the most despondent lyrics, Mould displays a sense of steadfast defiance. He sings not with desperation, but with a subtle anger indicating that he will not allow his present state of mind to fester— he realizes that the sooner he shakes his sadness the sooner his life will continue. So

When I spoke with Bob Mould last summer as he rested at home following his first solo tour, he was easygoing, open, and quick to laugh. He had emerged successfully.

The Bob: Workbook is a very emotional record. Was the writing and recording process successful in bringing about a carharsis? Are you happier now than at the time you were writing the record?

Bob: Ummm... maybe I'm happier about the things I dealt with on the record now than I was then. People always have this impression that I must be really anxiety-ridden or stressed-out or very emotional to write this stuff. And I guess in a sense I am, but maybe not as much as people think. It's always good to get things out of your system like that. It's not good to carry those things around with you forever. I'm a little bit happier now than I was a year and a half ago, that's for sure. It's been a long road, but it's been a good one.

The Bob: The album exudes a sense of loneliness on a few of the songs and on the back-cover photo that shows you sitting alone in an empty room. Were you by yourself in your house at the time that most of the record was written?

Bob: I was pretty much by myself all the time the whole year.

The Bob: Do you prefer being alone to surrounding yourself with people?

Bob: At that time I did, because I wanted to find out who Bob Mould was, as opposed to Bob from Husker Du, 'cause I already knew who he was, and I was sort of tired of who he was. I just really needed to put some distance between the Husker Du experience and what I was going to do next. I didn't go out at all. I didn't really see a lot of people. I stayed in touch with some friends— I write a lot of letters to people— but it was just really a time for me to decide what had happened and who I was going to be because of the things I had been through. And I really did not want to go out every night and pretend that nothing happened and have people keep asking me, "What are you gonna do now? Grant's doing this, Greg's doing this, what are you going to do." [Greg Norton was Husker's bassist.] I was like, I know what I'm doing but I want to make sure that I'm happy with what I'm doing. It's like getting divorced and getting married the next day. It works for some people but it didn't work for me. I just really wanted to have time to make time, to have time.

The Bob: This question might be too personal. In three of the songs on the album the subject of crying is brought up. Did you cry a lot over the breakup of Husker Du?

Bob: No, that's how I do it, I guess— with the songs. That is an interesting observation. I never thought of that.

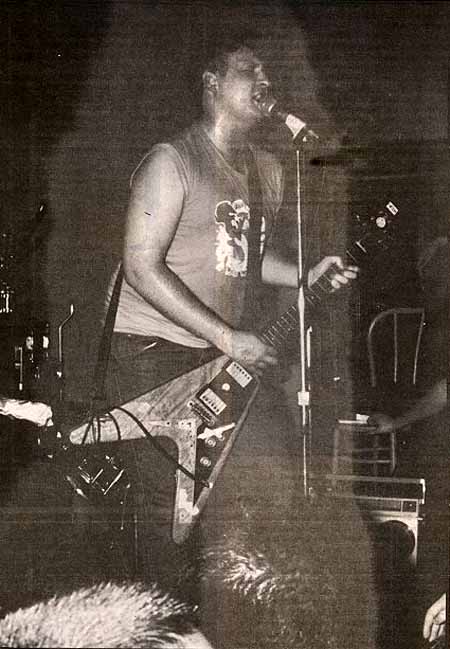

|

| Photo: Hard Times |

with Husker Du,

1985...

The Bob: Has the album allowed you to come to terms completely with the end of Husker Du? And have you been able to forgive whoever needs forgiveness by coming to terms with these things?

Bob: I think I came to terms with it before; sooner than now, that's for sure. I think now it makes a lot more sense than it did on the day that I left. I think the record has helped me find out what I am more than what I used to be. You can't deny where you've been or things that you've done before. You can't apologize for them either. As far as forgiving anybody, I don't think anybody was to blame. I don't think I ever blamed anyone for the breakup of the band.

The Bob: Have you seen Grant since the breakup?

Bob: Yeah, but we don't really have a lot to say to each other. We didn't have a lot to say to each other for the last two years of the band, so I'm not surprised that we have nothing in common now.

The Bob: So neither of you have tried to mend any broken bridges? Or is there no need for that?

Bob: I don't know if there were ever any bridges broken. I just grew away from that situation probably the same way Grant and Greg did. And that was one of the main reasons the band broke up— we all grew apart from each other and the only thing remaining was the fact that we were in the same band. So now that the band is gone we have very little in common. I really don't have a problem with either Grant or Greg. I just really don't feel like I have much in common with them.

The Bob: I'd like to shift the discussion from your new album to the music scene in general. The early '80s, for me and for a lot of other people, were a really exciting time in rock 'n' roll, especially in the underground or indie scene. But in the late '80s it doesn't seem nearly as exciting. As a music listener, has the excitement diminished for you as it has for me?

Bob: In some ways. But I think it's coming back around again. I've been hearing tapes from new bands, and there's some really good stuff going on again. But you're right, there was a bad spell there a couple of years ago, a really bad spell. I'm not sure what caused it. One theory that I'll lean on when questioned is the fact that the difference between indies and majors right now is non-existent. I don't know whether Husker Du or the Replacements or a few other bands I can think of are to blame for that because we all went with Warner Brothers. The majors got really hip all of a sudden— everything got hip and now nothing is hip.

I think it's a reflection of culture and of society more than it is the underground scene. People's thrills are few and far between now. It's like a fleeting

It's weird that it got commercialized so quickly. That was the one thing that was mind-boggling. It was like one day the Cars were hip and then all of a sudden Devo was hip and then the next day it was like "Decline of Western Civilization" was on videocassette. Things change so quickly. Now it doesn't seem to have much of an impact unless it's something of such a grand scale like the Guns 'N' Roses phenomenon, which is so outrageous that it really catches people's attention.

The Bob: What do you think of Guns 'N' Roses?

Bob: I don't care for it at all. It's a disaster waiting to happen. And I guess that's appealing to kids that live in the suburbs and kids that live in small towns and don't have to step over crack vials.

The Bob: Musically, can you appreciate the power behind the band, since you were once in the most powerful band in the world?

Bob: I remember seeing Aerosmith back in '75. I liked it the first time around. I guess I'm too old to appreciate what they do.

The Bob: Of all the exciting indie and underground bands of the early '80s, there's only a handful that are still around. And only R.E.M. and the Replacements have broken heavily into the commercial area. Why do you think more of those early '80s bands didn't make it?

Bob: Frustration with banging their heads against the door. On the other end of the coin, the unwillingness to put in the time that's required to really make an impact. Bands like the Replacements or R.E.M. or Husker Du or maybe even before that Black Flag, those bands really went out and tried to touch people with their music. They didn't stay home and make

|

| ...The pensive '90s. |

The Bob: I always thought the Meat Puppets would have some commercial success.

Bob: That was one band that I never realized why it didn't

The Bob: Do you think that Husker Du could have or would have broken into the commercial realm if they had kept at it?

Bob: I think so, maybe just out of sheer perseverance. It was real interesting. One of the strange conclusions I have come to out of all this is that my favorite record was the beginning of the end of that band: Zen Arcade.

The Bob: Why do you call that the beginning of the end?

Bob: It was the best record we made, but it was the one that we emulated. And when we went to Warner Brothers we couldn't change because we would have sold out. The poor band, stuck between some difficult places. Man, that's what you get when you look back.

The Bob: But you also built upon Zen Arcade in that you took the power of that album and made it more melodic and accessible on subsequent albums.

Bob: Yeah, I think that was a good thing. But it was so weird being in the band the last few years, a very strange situation. I was like, man, there was all these things that I wanted to see done with it, that I think we all wanted to see done with it that we didn't do. And I'm going to do them on my own now. I have started— phase 1 is in place. But god, that was a weird situation. People really wanted to hold on to the past. And in a way I think it made us want to too. It's weird. I'm certainly not ashamed of anything the band did, but, boy, looking back it's like, we could have done more. Something else should have been done.

The Bob: In 100 years when a college freshman is taking "Rock 'n' roll 101," where will Husker Du's place in history be?

Bob: "They used to be known as the fastest band in the world, then they were the loudest band in the world, then they were the next Beatles, and then they broke up. They had a fierce independent spirit about them that influenced a lot of the ways that people looked at music five years after they broke up." I don't know, 20 years after they broke up. It's hard to say what's going to happen. I think that it was an important band. It was a band for that period of time and maybe no other period of time. It's like the Velvets were, or the Stooges or the Dolls or the Pistols or the Clash or Blondie or whatever. Husker Du reflected the '80s, it reflected the Reagan years, and nothing. I can't re-create that myself. There're other bands that are carrying that torch now and more power to them. But man, I can't do it any more. I got to do what I got to do now.