SUGAR TURNING BITTER INTO SWEET

BY CHRIS MUNDY

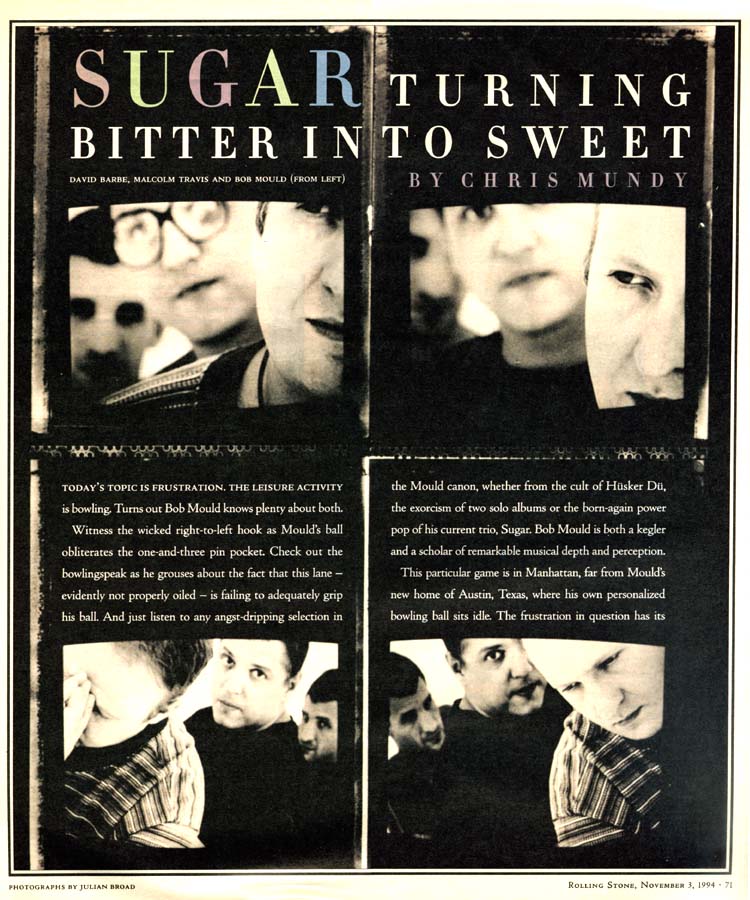

TODAY'S TOPIC IS FRUSTRATION, THE LEISURE ACTIVITY is bowling. Turns out Bob Mould knows plenty about both.

Witness the wicked right-to-left hook as Mould's ball obliterates the one-and-three pin pocket. Check out the bowlingspeak as he grouses about the fact that this lane — evidently not properly oiled — is failing to adequately grip his ball. And just listen to any angst-dripping selection in the Mould canon, whether from the cult of Hüsker Dü, the exorcism of two solo albums or the born-again power-pop of his current trio, Sugar. Bob Mould is both a kegler and a scholar of remarkable musical depth and perception.

This particular game is in Manhattan, far from Mould's new home of Austin, Texas, where his own personalized bowling ball sits idle. The frustration in question has its roots in Atlanta, home to the first attempt at recording Sugar's latest gem, File Under: Easy Listening.

"We're all pretty battered about this Atlanta stuff," says Mould. "It killed all of us."

Mould grabs a ball, holds it to the ultrabaggy T-shirt that hangs over his ultrabaggy plaid shorts and gracefully propels the orb toward the awaiting pins. Destruction complete, he continues.

"There were 17 songs done," Mould says. "There were some vocals left to do, and that was it. But it wasn't satisfying me. I erased everything." He pauses. "What are you going to do, keep the tapes on a shelf somewhere? Like you'd ever go into that room again. 'Yes, there is my abject failure.' It's poison, get it out of your life."

So began the trial that would lead first to catharsis in Austin, where File Under: Easy Listening rose from the dead in just five weeks, and finally ended in yet another bout with the personal demons that terrorize Mould after every completed project. "I have incredibly long spells of catatonia after I finish a record," he says with a look that mirrors the current subject matter. "And weird visions that are not pleasant. Sitting there, being wide-awake, imagining yourself falling out of an airplane." He pauses again. "Maybe the incredible emptiness I have at the end of a record is what I need to come up with things."

What Mould has been known for coming up with since Hüsker Dü built the foundation that today's alternative community is founded on are heart-wrenching pop songs played at warp speed, gripping tales of personal politics — commitment, betrayal, retribution — ushered forth under a shit storm of distortion and a voice echoing from somewhere just west of Mould's own private hell. File Under: Easy Listening offers that and more. With a sound residing squarely between the sleekness of 1992's Copper Blue, Sugar's debut, and Beaster, the 1993 followup EP that is every bit as brutal, bombastic and exhilarating as you would imagine an album about self-crucifixion could be, File Under: Easy Listening serves as a sampler platter for the band's many offerings.

There's "Gift," the album's opening ode to British shoe gazers My Bloody Valentine ("My dream tour would be Sugar and My Bloody Valentine playing football stadiums," says Mould). "We'd set up at opposite goal lines and play at the same time"), which shrieks as abrasively as any hospital nursery. The radio-friendly side of the band (granted, 1994 radio is willing to embrace pop songs draped in blankets of guitar squalor) rears its head on the first single, "Your Favorite Thing," while two acoustic ballads, "Believe What You're Saying" and Explode And Make Up" — both beautiful but bitter peeks at love in all its dysfunctional splendor — speak the album's last words. There is even an excellent tune, "Company Book," penned and sung by bassist David Barbe, and two lighthearted songs, "Gee Angel" and "Granny Cool," that amazingly enough, give a glimpse of Mould out of self-flagellation mode at the same time they embed themselves in the listener's subconscious. It's a veritable smorgasbord of all things Sugar. And it's sheer luck that the album exists at all.

"In Austin it was best to just leave the problems alone and get the job done," says Barbe, when asked a few weeks later about the Atlanta debacle. "There were also a lot of people around, and that's no way to to discuss something like that, especially between friends. If we were just partners in a business, like an alarmingly high number of band personnel are these days, then it would be different. But the biggest concern was if this shitty experience was going to sabotage our friendship."

In the end, all was salvaged. Not that Bob Mould is ever satisfied. He prepares to pick up another spare — having once again left today's major nemesis, the seven pin, standing — and eyes the lane like a kid staring down a schoolyard bully. Later, over too much coffee, he will show us just what he sees.

"This is weird," Mould will say. "I'm sitting here transitioning into middle age with this totally abrasive record. I'm 33. It's a young person's game, I know that. But the art of expression is for anybody. I get very flustered when I turn on the television and radio and I hear things that are very easy to recognize and reference. You just say, 'This sucks. Time has caught up to me.' That's a bummer. I wonder if this means that I've been standing still for 10 years."

TIME WAS WHEN THE MEMBERS OF SUGAR, ESPECIALLY Mould, went out of their way to say that this was a band. "It's not just Bob and a couple of other guys," they would assert, as if they were really fooling anybody. "We're a band and we're all on an identical mission." That time has passed.

"We've come to a realization," says Mould. "For all intents and purposes, it's my deal."

Not that Barbe, 31, and drummer Malcolm Travis, 41, are random session men. By spending most of the '80s crisscrossing the country as one-third of the punk band Mercyland, Barbe has paid his dues in full. Same goes for Travis, who earned his merit badge drumming for the seminal Boston garage band Human Sexual Response. It's just that Mould's vision is of a rather intense nature, and let's just say that sometimes it doesn't play well with others.

Certainly the breakup of Hüsker Dü in 1988 was fraught with its share of clashes between Mould and the band's other songwriter, Grant Hart (currently of Nova Mob). It is a period of Mould's life, however, that he has long since put to bed. Nowadays, when the subject of the breakup arises, he laughs. "There's people who think I'm still sending missiles at Grant," says Mould. Sorry to disappoint you, but I took care of that about five years ago. Check out side 1, song 5 on Workbook." (Lest any fans injure themselves rushing off to look up the reference, Workbook is solo album No. 1; the song is "Poison Years.")

The true toll Mould's 13-year career has taken is physical. Mould's hearing has deteriorated to the point that on the road, because his ears ring, he sleeps with the television on. Blessed with the solace of his own home, he continues to blare the TV because "the silence is unnerving."

"I know I'm reaching the end of what I can do because of my hearing," says Mould. "I don't want to get to the point where I'm draggng myself onstage. Sometimes I feel really old because of all this. Physically and mentally, I feel beat to death sometimes."

It is the curse of Mould's fierce commitment — all the way down to refusing to wear earplugs onstage — that has wreaked physical havoc on his body. That commitment is also the blessing that grants him the power that has defined his unique songwriting gift. So it should be no great shock that a conversation with Mould occurs with the heightened focus of a staring contest. He is articulate and ripe with thoughtful insights (born in upstate New York, Mould attended Macalester College, in St. Paul Minn., on an academic scholarship). He professes a pride in his own work that although quite accurately assessed borders on the egomaniacal. He is willing to shoulder criticism and is not afraid to laugh out loud. Even this, however, seems to burst forth with an almost unsettling intensity.

"Bob certainly has a relaxed side," says Barbe. "He's one of the kindest, gentlest people I've ever known and one of the most intelligent. But he can be very intimidating. If he was happy-go-lucky all the time and then wrote these deep, brooding songs, you'd wonder if one was a put on."

Travis is more succinct. "Even with the band, Bob seems kind of private and personal," he says. "He needs his space, so we give it to him."

That leeway extends all the way into the business of Sugar, where Mould not only owns his own publishing catalog but actually owns all the music, licensing it to his record label in a manner similar to deals usually struck in the world of independent film. Suffice it to say that Mr. Mould is in charge. "If people understood what goes on in the music industry," says Mould, "they'd understand my demeanor and my reputation for being recalcitrant and a control freak."

Point well taken. Most important, the business setup is a situation supported by both Barbe and Travis. Which leads us to another reason why Sugar is inevitably Mould's soapbox: simple geography. All three members live in different cities. So while Travis toils in Boston (where he works part-time in a record store and plays in two other bands, the Flower Tamers and the Wheelers and Dealers), Barbe and his wife raise their three children in Athens, Ga. "Bob's basic philosophy is that people's lives come before career moves," says Barbe, who also plays in a hometown band, Buzz Hungry. "I most definitely approve of that. Anything in my career is done according to what is in the best interest of my children."

Meanwhile, back in Austin, Mould is busy serving his obsessive drive by continually placing song after song upon its altar. A typical day entails working at the business office until 4 p.m., relaxing briefly and then napping. The task of relaxation accomplished, Mould throws on a pot of coffee and begins his day anew by heading to his studio to write from 8 p.m. until 3 a.m. It is certainly not difficult to see how Hüsker Dü managed eight albums (two of them doubles) in its nine-year career. Or why Mould — keep in mind you've witnessed him sober — quit drinking and doing drugs eight years ago out of fear that he was penning his own obituary.

"That was a real big life change," says Mould. My stopping drinking was the end of Hüsker Dü, much more than anything else. I think it set me apart. I was 25, and I knew my body couldn't handle it much longer. I didn't want to die. Now I don't worry about alcohol. The allure of speed looms much larger than the allure of alcohol. Speed is just too good. I still get the taste in my mouth. It's just plain too good."

And with that, talk turns slowly to the tendency of artists to willingly live their lives in the press. It is a practice, Mould explains, that drains his faith in the profession he has chosen.

"I don't give out a lot of details about my private life because I enjoy being an observer," says Mould. "I know when I'm being observed, and I don't mind. But if a line is crossed, I can't go out anymore."

Asked what role he's expected to play in his life as the observed, Mould pauses and then launches into a very focused, if not altogether rehearsed, soliloquy.

"Everybody wants me to carry the gay flag," he says. "My sexuality was not a choice, and people have really wantd me to make an issue of this. I'm not a freak. I'm a human being. I'm a writer. I've never understood the gay lifestyle. It's not part of what makes me a person. If I decide to have sex with a man, I'm not sure that absolutely means that I have to be a gay role model. There are people who are much more qualified than I am to speak on that subject. The only thing I can speak on with total assuredness is my work. Anything beyond that, carrying a flag — whether it's Lollapalooza's flag or Queer Nation's flag — I'm sorry, I can't help you. My sexuality is no secret. It really never has been. But haven't I given you enough over the last 13 years? What about this incredible body of work? Those songs are for everybody. The work I share with everybody."

IF THIS PARTICULAR AFTERNOON CAME COMPLETE with a bowling trophy, it would be resting in the hands of Bob Mould. But since no medal is available, Mould — who, it must be noted, has the distinct advantage of having bowled 30 games a week in his youth — is celebrating with two of his favorite things: coffee and cigarettes.

Tomorrow, Mould will fly to London to throw himself into the belly of the music-industry beast. This day, therefore, is for practicing the art of putting Sugar in perspective. You see, Mould is in the precarious position of being both a forefather of and a peer to the gaggle of alternative bands hogging the upper echelon of the music charts. With Hüsker Dü he helped set the mid-'80s standard for the art of melodic chaos by combining the velocity of punk and the sheer volume of heavy metal with pop melodies and confessional lyrics that sidestepped the usual nihilism of such noise. These days, it might seem commonplace. Back then, it was downright revolutionary. As a solo artist, he first stripped away the armor of his guitar noise to create Workbook, a stunning acoustic purging of the Hüsker legacy, before diving into the abyss of 1990's Black Sheets Of Rain, an album whose title seems upbeat when compared with the explosion of its musical and lyrical content. When speaking of his career, Mould claims that "there's everything before Workbook and everything after — that's the turning point."

Now, with Sugar, Mould is reaping the rewards of a decade of trailblazing. Yes, he's just one of the many people cashing in on all the groundwork laid by bands like Hüsker Dü and the Replacements — but he was actually in Hüsker Dü.

"The entertainment industry and music is full of a lot of impostors," says Mould. I see a lot of people willingly and unwillingly having idiosyncrasies in their lives magnified into freak elements simply to land the cover of magazines. What have these people done for anyone?"

He draws forcefully on his cigarette.

"I see other people just picking up their paycheck, and then in a few years they'll go on to something else," Mould says. "That freaks me out. Music makes me realize I'm alive. This is my life. Those people don't know how lucky they are that they have anyone to listen to their music because they have nothing to say."

Besides the occasional youngster like Kevin Shields of My Bloody Valentine, Mould considers most of his contemporaries to be his fellow travelers from the years before punk broke: Mike Watt of the Minutemen and fIREHOSE, the members of Sonic Youth and Soul Asylum. It is to this inner circle that the Sugar frontman occasionally rants about not letting creature comforts deter creativity.

"I talk at them," says Mould, laughing. "To a degree, people listen. I'm happy to hear that R.E.M. is going to lighten up a little bit and get out of the tomb for a while. I was talking to Michael [Stipe] a while back, and I said, 'You know, it's about time to stop mumbling.' When you hear 'Pretty Persuasion' on the radio, it still sounds pretty radical. It's not like I want them to do that again. I just want them to remember the essence."

Which brings everything quite neatly back to Sugar. The sounds on File Under: Easy Listening — album No. 13 in Mould's 13-year career — still pulse in the very marrow of what Hüsker Dü set out to accomplish. Whether juxtaposed with the current live Hüsker retrospective, The Living End, or or placed along other great bands on the continuum, such as the Pixies or Nirvana, Sugar still hold true to a musical ideal. But don't bother telling Mould. As it has been mentioned before, he is perfectly aware that he is both a legacy and an artist of enduring legitimacy.

"I'm not waiting for someone to pat me on the back," says Mould with an uncharacteristic grin, "I've got a lot of pride in my work. I hate to toot my own horn, but..."

He leans back in his chair, spits out a laugh and imitates a tugboat. "Toot, toot."