|

and a Black Flag

performance. There is a feeling that outbursts of crowd violence are

imminent. Sometimes the audience spits at Rollins. Sometimes he jumps right

into the crowd, a swelling, moving, slam-dancing group of kids. Rollins has

been known to punch out a particularly obnoxious and unreasonable heckler who

wants to fight and will not let him perform. "My thing is real

confrontational," says Rollins of his performances, which have, on occasion,

left him with broken bones. "I mean, I don't like to go beat people up, but

I like to be real close. Bring it home. If someone wants to touch me, kiss

me, hit me, stab me, talk to me, sing with me, they should be able to lean over

and do it!"

Perhaps more than anything else, Black Flag wants to shake up its audience. "I

find it really distasteful to have a band that plays to me what I want to

hear," says Greg Ginn. "That's no kind of expression. We don't play to

satisfy an audience. We play what we want them to hear. If you love your

audience, you try to bring them something they don't already have. You don't

play totheir current sensibilities and not give them anything that would

threaten them. To me, that shows a total disrespect for an audience.

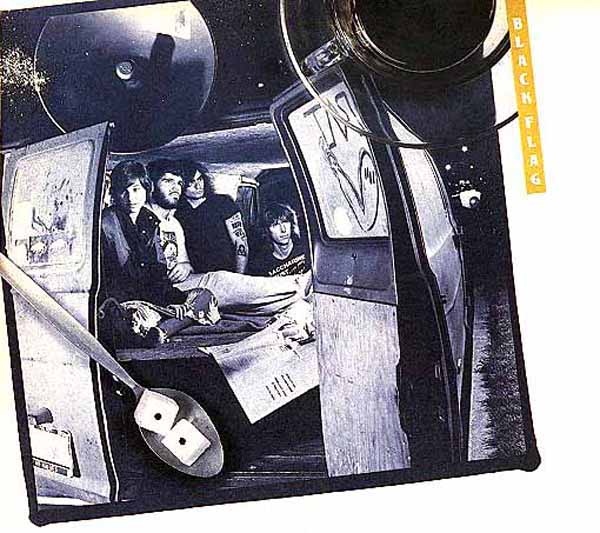

"IF YOU WORK FOR SST

Records you

have to be prepared to sleep on the floor," says Jordan Schwartz, 21. That's

just what Jordan and Black Flag manager Chuck Dukowski do. They sleep on the

floor of the messy office in Redondo Beach, which, along with a cramped,

low-ceilinged downstairs rehearsal room, serves as Black Flag's base of

operations.

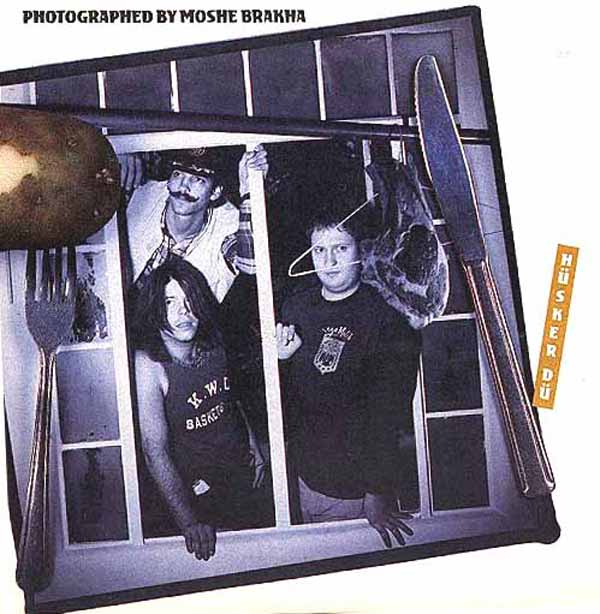

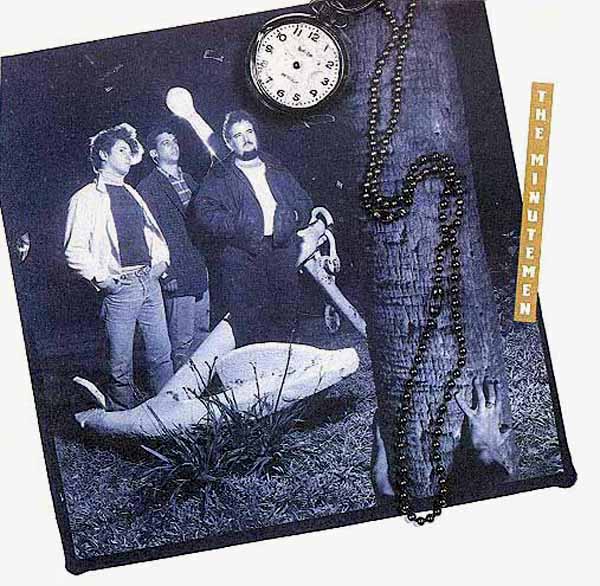

SST is the most important underground record label in America. As the Los

Angeles Times noted not long ago, "The company [SST] has matured into a

showcase for some of the best alternative rock bands in the country." In

addition to Black Flag, other acts include the Minutemen, the Meat Puppets and

Hüsker Dü. In its five-year existence SST has released over forty

recordings, eighteen of which are LPs. Last year alone SST released four

albums by Black Flag as well as double albums by the Minutemen and by

Hüsker Dü and albums by the Meat Puppets, Saccharine Trust and St. Vitus.

SST is just one of a group of underfinanced, low-budget underground labels

— San Francisco's Subterranean and Minneapolis' Twin/Tone are two

others — which have been recording bands that the major labels have

either overlooked or dismissed as uncommercial. "Me and my friends wanted to

record the punk-rock scene," says Steve Tupper, 38, explaining why he formed

Subterranean Records [Cont. on 124]

drugs stronger than marijuana. Some concern themselves with eating healthy

food and staying fit. Some don't drink. Black Flag guitarist Greg Ginn, 31,

and Flipper singer-bassist Bruce Lose, 26, are vegetarians. Black Flag and

Hüsker Dü pride themselves on being "responsible" — a claim

Johnny Rotten would never have made for himself.

Unlike the punks of the Seventies, this new generation also has some respect

for the hippies and the values they embraced in the Sixties. Around the Black

Flag office and rehearsal room, in Redondo Beach, California, one frequently

sees long-haired roadies wearing Grateful Dead T-shirts and playing

Aoxomoxoa or Workingman's Dead on their boom boxes. Greg Ginn

says one of his dreams is for Black Flag to open for the Grateful Dead. "It

seems like a lot of the things that happened in the Sixties — freedom,

having an open attitude — are being replaced by a new puritanism,"

complains Ginn. "It's time to loosen it up. A lot of stuff done in the

Sixties was important."

IF YOU SAW HENRY ROLLINS hitch-hiking, you wouldn't stop to pick him up.

He looks like a psychopathic hippie, part Jim Morrison, part Charles Manson. Real

|

bad news. A BORN TO LOSE kind of guy.

Get close to him — it's downright scary. Eyes that bore right through you.

Hair, a tangled mess that falls past his shoulders, down his back. Ragged,

ripped clothing. Lots of tattoos: skulls and snakes, ghouls, a spider, a

bat. And, etched across his upper back in inch-high letters, Henry Rollins'

philosophy of life: SEARCH & DESTROY.

"I think you really got to look at it deeper than surface level," says Rollins.

I mean, the way I look — this is only skin. Perhaps, but Rollins'

image — and the way it alienates him from so much of socirty — in

many ways characterizes the relationship between Black Flag and mainstream

America. "I guess we offend a lot of people," Rollind has said. "The hair

length, the way we look, the way we dress isn't conducive to one-way thinking."

An aura of dark violence hangs in the air around Black Flag, like soot from a

turn-of-the-century factory smokestack. Sitting in a hamburger joint down the

street from Black Flag's office, Rollins wolfs down a burger and

stares at several kids glued to videogames. "Life, for a lot of people, is a

very surface-level experience," he says. "I see these lard-assed kids in front

of these

|

videogames. You know, as close to any kind of real destruction as

they'll ever get is to put a quarter in and blow something up. When I see

complacency, I just got to fuck with it. This is such a soft place to live.

A lot of places to me are like a big open throat waiting to be cut. You can

walk into a lot of these houses and kick the door down and just take it. It's

yours. I'm not going to be cutting nothing, because that's not my life. But

I'm in favor of something else for me."

Black Flag has been associated — unfairly, its members claim — with

punk violence since the late Seventies. People have accused the band with

being sexist, racist and fascist. The group was forced to move out od three

L.A. communities. "Our whole thing has beenmade out to be brutal, fascistic

and violent," says Rollins, who does not drink or use drugs. "Those are three

things that we're very much not into at all. We're not violent. We're

not evil. We don't like to see anybody hurt at any time. I don't like to see

violence at anybody's shows. I've seen more violence at Van Halen than at any

of our gigs."

While Black Flag's music no longer resembles the punk of the past, there

are similarities between a late-Seventies Sex Pistols concert

| |